2020 will be remembered for many things. The pandemic and flooding among them. It will also be remembered as the year they took planning away from the people.

The government’s proposals in the white paper Planning for the Future and associated documents are bold. They will transfer many local planning powers from councils and communities to Whitehall and the planning inspectorate in Bristol. Ministers want planning by checklist instead of considered, albeit sometimes difficult, planning deliberations that lead to quality developments.

There are sensible ideas in the government’s proposals but they are countered by its determination to take democracy and localism out of planning.

In 2011, when the National Planning Policy Framework was first mooted, countryside and environmental campaign groups joined forces with professional bodies to oppose the framework’s most damaging measures. The ‘broadsheets’ covered the campaign daily. The Telegraph ran a “Hands Off Our Land” campaign. It has not been not like that in 2020 and the reaction to Planning for the Future has been muted.

Perhaps people are still reeling with shock. After all, Planning for the Future doesn’t aim to fiddle with the planning system. It wants to shred it and replace it with new principles and different ways of working. (The proposals are explained in this CPRE briefing and video.)

Local plans will be produced more quickly and will be simpler and shorter. That’s good. Design codes aimed at “building beautifully” will be introduced. That’s good. Ministers want to digitise the planning system. That’s also welcome.

Our leaders complain the public doesn’t understand the planning system. This is their excuse for proposing to restrict community involvement to the local plan stage. That’s the stage at which England’s urban and rural landscapes will be allocated into one of three zones. Under this scheme, building will be limited within Protected Areas such as AONBs and national parks. But in Growth and Renewal Areas, councils will be expected to approve any development that ticks whatever boxes were agreed with the planning inspectorate at local plan stage. In these areas, residents will have no role in individual planning decisions. Council planning committees will become an irrelevance.

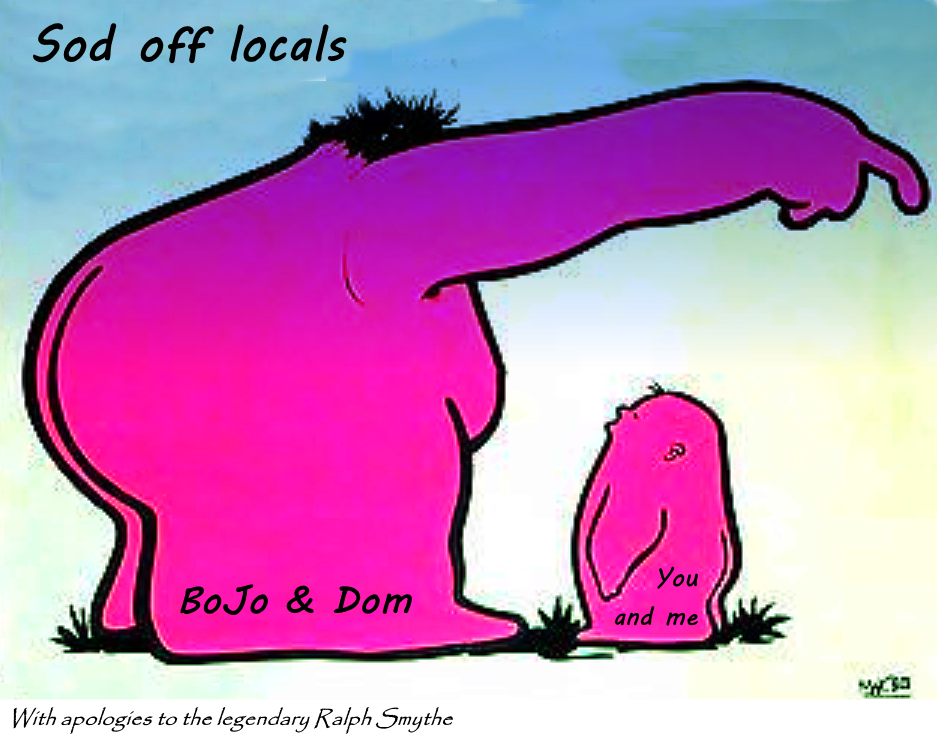

Ministers and their advisers rage against the discretionary character of the planning system. Discretion is localism to you and me but ministers want local plans to set inviolate rules instead of outlining planning policies capable of interpretation and flexibility as needed. Development management policies – the rules that control how local plans are implemented – will be nationalised. One set of rules for all regardless of how well they fit local communities.

Local plans will be pro-forma. At one extreme of the government’s options, there will be no right for communities and councils to be heard during the examination of the plans.

Of course, our current planning system is too complex. Of course, it needs simplifying. But that should not be at the expense of local voices. Changes should not transfer power from local communities to the anonymous corridors of Whitehall and Bristol.

Instead, ministers must stop giving lip service to localism and ensure local democratic debate remains at the heart of our planning system. We must trust community voices.

The white paper, Planning for the Future, does the opposite and aims to destroy localism in planning.

The consultation on Planning for the Future runs until and the consultation on Changes to the current planning system until 1 October 2020.

A second article on the implications of these proposals for housing will be published tomorrow.

This article was first published on Lib Dem Voice.