This is the second article on my misadventure with a stroke and my adventures in Hereford Hospital (the first article). It has some serious messages but it also tells of the funnier moments and the wonderful camaraderie amongst the medical staff in a challenging environment.

Within hours of arriving in A&E, I was moved to the acute stroke unit on Wye Ward. I couldn’t stand up and was transferred into a bed using a Pat Slide. The bay I was in was mixed and was occupied at that point by two men and two women. I write more on mixed bays below.

Although my mind was unaffected by the stroke, I was confused by the different environment. Who was who, what the routine was and how badly the stroke had affected me. But I soon learnt the basics. I was confined to bed. There was no possibility of sleep, the bay was busy 24-hours a day. My blood pressure, pulse rate and sugar levels were checked every four hours. I had the pleasure of a jab in the stomach at midnight. On top of that there was a constant, but welcome, stream of specialists, including Dr Jenkins, who was to oversee my rapid recovery.[1]

The nurses were superb. I really admired their camaraderie in sometimes difficult circumstances.

As well as the frequent drug rounds, the nurses and assistants monitored food intake. After recording what I had eaten at the three set mealtimes, they quizzed on the basic bodily functions. For the first couple of days, they counted everything in and everything out.

I began to improve rapidly. The stroke hit around 4.30am on Thursday. Twelve hours later I could lift my left arm and left leg. It was a struggle but a real improvement.

On the second day, the physios came in the afternoon. I could hold my left arm up for the requisite ten seconds. I could grip with my left hand but not enough to hold anything heavy. My legs worked, though my left leg was weak. I was given permission to walk short distances around the ward. I rather nervously asked if I could now use the toilet rather than a bedpan. I metaphorically leapt for joy when I was given permission – a real leap for joy would have been both impossible and unwise.

There was quite a turnover in this acute bay. Most patients were too ill to converse with. Edna was the most distressing and most distressed. The poor woman was suffering from both a stroke and dementia and was completely unware of where she was. She continually shouted for help and screamed herself into exhausted sleep, but she never slept of more than an hour or two at a time. None of us did.

By this point, I was the only man in the bay. It was often quite hot and the ladies, all of whom were very unwell and largely unaware of where they were, tended to pull at their clothing. Nurses rushed around covering them up, saying, “there is a man on the ward.” I felt very sorry for the women, who would not have had this problem in a single sex bay.

On another occasion, in another bay, a man failed to get to the toilet in time. There can be no criticism here. It is my experience that bowels declare UDI the moment they pass through hospital doors. But having soiled his trousers and underwear, he wandered around in just a shirt that failed to cover his modesty. By this point, I was in a male only bay, so we laughed it off with barrack room humour until the nursing assistant persuaded him to dress – and that was no easy task.

I understand that under times of exceptional pressure, mixed bays are the only option. But I not sure that politicians, and perhaps some senior health managers, recognise how stressful it can be for older people with cognitive impairment. Although being in a mixed bay concerned me not one jot, it was clear many patients older than me were distressed by the arrangement. That cannot have helped their recovery.

My stroke, caused by a clot in an artery on the right side of my neck, had proved to be minor. On Friday afternoon, I asked to go home, pointing out it would free up a bed. This was politely but firmly refused. The clot had yet to fully clear and there was a danger it would move up to my brain. And I live on my own. That was regarded as a high risk factor.

On Saturday evening, I was told I was to be moved from the mixed bay. I hadn’t slept for two nights and was told, “You need to sleep”. I couldn’t disagree. I was also recovering well. Saturday was a busy day with nurses rushed off their feet, so it was Sunday before I was wheeled down the corridor to a male only bay.

There I met Harry, who had a degree of brain damage. He was a very intelligent and erudite man who was utterly frustrated by his condition and confinement. He was in a near permanent state of fantasy. At times he pretended – and perhaps even thought – he was a judge. We hammed that up a bit, though I was always regarded as the junior clerk.

Harry and I were getting on well and we had good banter. Early on Tuesday morning, he mentioned escaping. Harry did have a real problem with escaping. He refused to wear pyjamas and lay in bed fully dressed, even wearing his shoes. Every hour or so, he got out of bed and went for a walk. We had a care worker on the bay 24-hours a day to ensure that he did not leave the ward, which he had done on occasions when staff were rushed off their feet.

On Sunday night, it was approaching midnight when he announced he was going to the bus station to get a bus to have lunch with his daughters. It took some persuading to get him to recognise that there were no buses at midnight on a Sunday.

Escape was always on his mind, so I was not surprised when a couple of days later he suggested over breakfast that we plot an escape. Conscious of his wandering habits, I told him that was not possible. The conversation went something like this:

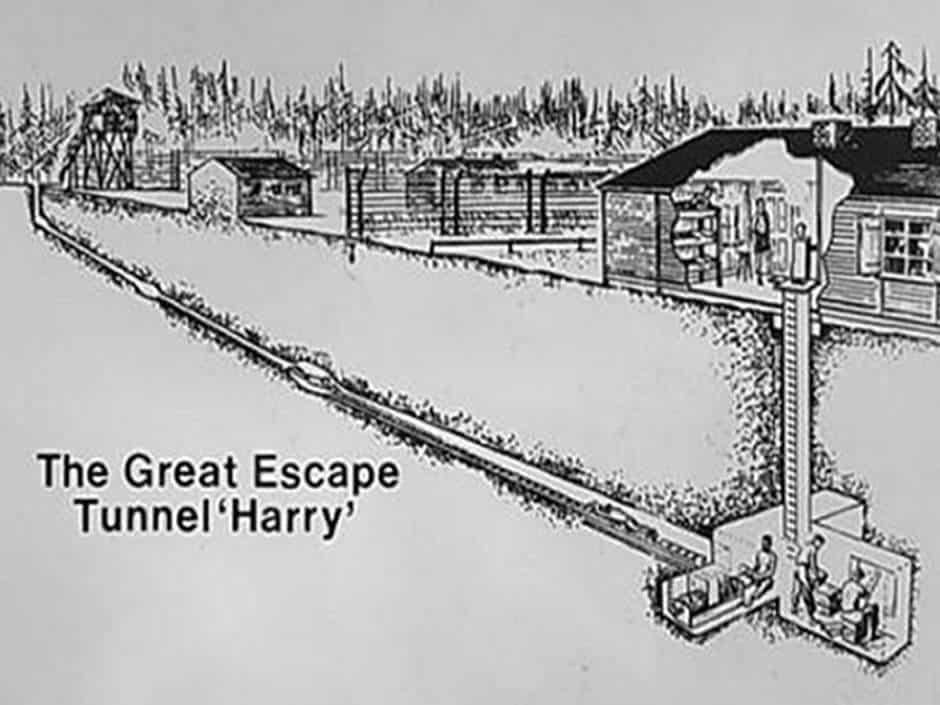

Me: “Harry, we can’t escape. The tunnel we were digging under my bed has been discovered.”

Harry: “How did they find it?”

Me: “The nurses found the concrete we were smuggling out in the bedpan.”

We laughed and laughter is a good medicine in the face of adversity.

The previous day I had undergone an MRI scan. The noise in the scanner is akin to being in the mosh pit at a heavy metal concert. But I was so tired, I slept through most of it. On Tuesday morning, Dr Jenkins arrived early and took me for a second ultrasound scan on my neck. It was clear, as was the MRI scan. I could go home!

Leaving was a surprisingly emotional experience. Staff and patients had all got on well and my treatment cannot be faulted. I had had a lucky escape and I have made a full recovery.

My recovery was greatly helped by the support I received from friends, family and the huge crowd of supporters on Facebook. Mel the Collie was well cared for and was promptly returned when she made her own bid for escape – I think she had gone to look for me.

Life is returning to normal. Thank you everybody and my special thanks to everyone at Hereford Hospital and the ambulance crew that ferried me there.

Notes

[1]. This is the only real name used in this article to preserve the confidentiality of patients. I have also changed some minor details for the same reason.

Wonderful! Hope you sent a copy to the Drs and nurses at the hospital t’would be a great morale booster.

And my real worry had been Mel – last seen at the door as you disappeared off to hospital. Glad to hear you are safely reunited.

And I hope you are following to the letter all instructions to guarantee your future good health.

So visibly described Andy and very glad to hear you re on the way to recovery … with the best help you can hope for … Mel.

But as to “I understand that under times of exceptional pressure, mixed bays are the only option. But I not sure that politicians, and perhaps some senior health managers, recognise how stressful it can be for older people with cognitive impairment.” With their salaries, I doubt the will ever experience the medical reality faced by us plebs.